Introduction

It has been well reported that diet impacts behaviour in horses; however, until recently there has been a lack of studies investigating the reasons behind this. Many reasons have been proposed to try and explain the impact of diet on behaviour in horses, but it was not until research into the impact of gut microbes on behaviour began to emerge that it became evident that this may be an explanation for the effect of diet on behaviour in horses given the emerging evidence on the impact diet has on microbes in the hindgut of the horse.

It is well documented that diet has a significant impact on the composition of the microbes in the gut both in horses and other species, including humans. It has been seen in other species that undigested starch entering the large intestine is associated with increased anxiety and aggression. It was initially thought that this was due to digestive discomfort; however, further studies highlighted that the composition of gut microbiota had an influence on behaviour and that the effect the starch had on behaviour was as a result of changes in microbiota, rather than fully attributed to digestive discomfort. In horses, there has been anecdotal evidence that diets high in starch can lead to behavioural changes, with horses reported to be “spooky” and “on their toes”.

As discussed in previous articles, horses have evolved to eat a diet high in fibre on an almost continuous basis. As such, horses have a limited ability to digest starch in the small intestine and any undigested starch passes to the large intestine where it is fermented by the resident microbial population. Thus, contrary to previous thoughts around these higher starch diets providing extra energy that resulted in less desirable behaviour, current thinking is around the impact the undigested starch has on the hindgut microbes, which then impacts on behaviour. I’m sure many of us will have owned or known of a horse that is a bit “lazy” and lacking in forwardness and will no doubt have tried to add additional energy to the diet to address this. What you have likely found is that your horse is no more forward going but is much more likely to spook.

Research at the University of Glasgow’s School of Veterinary Medicine has shown that horses fed diets containing starch, such as concentrate feeds containing cereals grains (oats, barley, maize), are likely to be more reactive than those horses fed a fibre-only diet. When horses are fed the same amount of energy but in different forms, starch versus fibre, their heart rates and reactiveness are greater when fed starch compared to fibre-only. Horses fed starch were less predictable in their behaviour compared to those fed a complete fibre diet and were therefore more difficult to handle. The horses on the fibre-only diet were also more settled and less reactive compared to those fed starch. The group of horses fed the starch feed were also observed to be more tense, nervous and unsure about their surroundings. It is important to note that the amount of starch that was fed was less than many leisure horses receive in their ration, which shows that even small amounts of starch in the diet can have a significant effect on your horse’s behaviour.

Grass growth

In cold and temperate climates, such as the UK, most grasses in your pasture are cool-season grasses. These types of grasses grow rapidly in the spring, when soil temperatures reach 4-6oC, and less in the summer months as conditions are much dryer followed by another growth spurt in the autumn.

Grass needs energy to grow and it obtains this energy from sugars (also known as saccharides) that it produces via photosynthesis. Photosynthesis is a process whereby plants convert light into simple sugars. The plant then takes these sugars and converts them to more complex sugars, some of which are stored as an energy source for the plant. These types of sugars as called water soluble carbohydrates (WSC). The WSCs in plants consist of simple sugars and also fructans.

You may recall from previous articles that horses lack the enzymes in their small intestine to digest fructan and consequently fructan travels to the hindgut where it is fermented by the microbes. In a similar way we want to avoid high amounts of starch reaching the hindgut, it is the same for fructan. The main difference here though is that starch can be digested in the foregut and we can implement feeding management strategies to maximise this small intestinal digestibility of starch. Conversely, we cannot do this with fructan, which is why we need to ensure we manage our pastures and turnout effectively. However, the main point here is that if the behaviours we see when horses are fed starch are due to the changes in the gut microbes and we know that fructan entering the hindgut can impact on that environments in the same was as starch does then this may explain why we see horses “on their toes” and more “spooky” in spring when there is more grass in the fields.

Nutritional composition of spring pasture

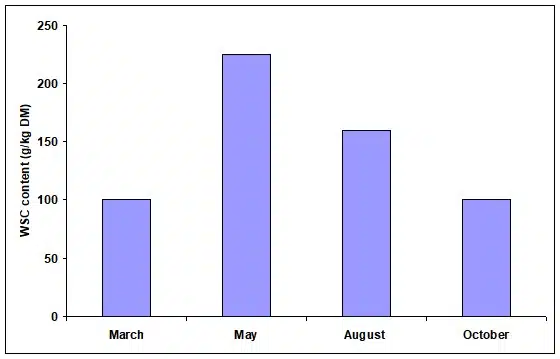

The nutritional composition of pasture is highly variable and dependent on plant species present, management and the environment. The WSC content of pastures is incredibly variable, not just on a daily basis, but on an hourly basis – depending on the weather. The WSC content of pasture can range from 5 to 40% and is weather dependant. Time of year (season) has a major impact on WSC levels, along with the environment. The graph below shows that, generally, WSC contents tend to be lower in early spring, higher in May, but may also be present in substantial amounts in August before dropping back around October time (Figure 1). However, it is important to recognise that this is highly variable and substantiates the need for our understanding of how the environment impacts on pasture WSC levels.

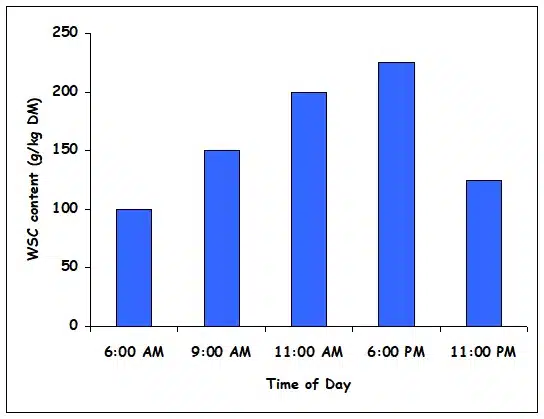

Essentially, the WSC levels in pasture are a result of the balance between photosynthetic activity (i.e. the amount of WSC produced) with the amount used by the plant. This is affected by light, temperature and nutrients. For example, if it is bright and warm then the grass will make WSC and use it to grow. Conversely, if it is bright and cold then the grass will produce WSC, but not use it and therefore the WSC is stored in the plant. Water is also required for growth and therefore if it is bright and warm, but little water (rainfall) then the plant cannot grow thus WSC is stored. In fact, WSC levels change throughout the day, with lower levels present in pasture overnight and higher during the day, usually peaking around mid to late afternoon (see Figure 2). However, again this is highly variable and depends on the weather that day.

Summary/recommendations

It is difficult to manage/monitor grazing intake in horses, especially when they are turned out 24/7. Studies have even shown changes in the horse’s microbial populations in the hindgut when kept at pasture 24/7 and 365 days of the year. As discussed in my article on “managing your horse’s pasture” stocking density and grazing management are very important to manage your horse’s grass intake and bodyweight. In terms of the impact of pasture changes on the hindgut, studies conducted at the University of Glasgow’s Veterinary School have showed yeast supplementation can help maintain a healthy hindgut when forage composition is changed. The impact of this change on microbial populations in the hindgut of the horses was reduced when yeast was fed.

Figure 1: WSC content of pasture at different months of the year (Longland, 2007).

Figure 2: WSC content of pasture throughout the day (Longland, 2007).

Article written for Premier Performance CZ Ltd. by Professor Jo-Anne Murray.